Around the world, approximately 1.2 billion people natively speak a form of Chinese, yet very few of Martin Luther’s writings have ever been translated and made accessible to them. In the mid-1990s, a group of Chinese Lutherans and scholars undertook that monumental task.

The impetus for the project came from the Rev. Dr. Won Yong Ji, a Lutheran missionary from Korea who translated numerous works of Martin Luther into Korean. As a result of his prompting, a committee was formed not only to translate Luther’s Works into Chinese, but also to distribute them within China — a difficult endeavor.

“Getting [Luther’s Works] into the mainland is a delicate process,” said the Rev. Dr. Henry Rowold, a retired LCMS missionary to Asia and professor at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, who has helped with the project since its inception.

Getting the books into China required a committee composed of members from both inside and outside of the restrictive country.

Setting the Course

Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, worked with The Lutheran Church—Hong Kong Synod (LCHKS) and the China Evangelical Lutheran Church in Taiwan to select four Lutheran scholars for the committee. Then, in cooperation with various educational institutions and professors, four scholars were chosen from inside China.

Those inside China “were all professors who knew and taught in the area of Reformation history,” Rowold reported.

Once selected, the members of the committee for the Chinese Edition of Luther’s Works (CELW) faced a number of challenges. One of the biggest was that they needed to translate each book into two different sets of Chinese characters.

In the 1950s and 60s, the Chinese government created a simplified set of Chinese characters. As a result of this change, the Chinese language in mainland China developed differently than other Chinese-speaking locales, such as Hong Kong and Taiwan. The CELW project required editors inside and outside of China to ensure the highest-quality translation into both simplified characters (for mainland China) and traditional characters (for Taiwan and Hong Kong).

Double the Work

The CELW editors were committed to producing works in “good modern Chinese,” Rowold said. Creating two separate volumes for each work requires significant effort and resources.

Few people know the process better than the Rev. Sam Yeung, director of the LCHKS Literature Department and pastor of Proclaiming Grace Lutheran Church. Yeung helps recruit and manage the editors and translators who work on the CELW project.

He explained that the process of converting from traditional to simplified characters requires more than pushing a button. Significant variations occur in the use of and number of characters for a given word and even the forms of speech.

The names of people and places provide a good example. The number of characters used to spell “Samuel” might vary by one or two characters from traditional to simplified. Furthermore, censorship practices in China might require a different spelling and pronunciation from that of simplified Chinese outside of China.

Inside and Outside of China

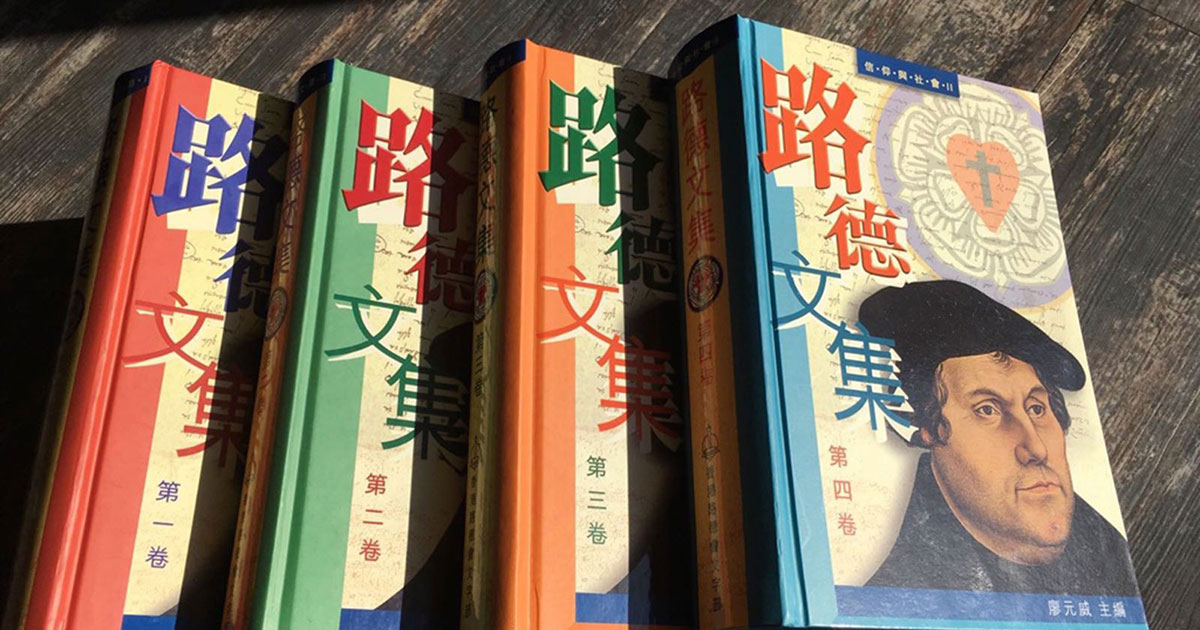

The complexity of the process and staff turnover in the early 2000s created significant setbacks. However, the committee persevered and completed Volumes 1 and 2 in both traditional and simplified characters. So far, more than 1,000 copies have been sold of each volume in each language, and the simplified versions are in the process of being reprinted in mainland China.

Volumes 3 and 4 in traditional characters also have been published, and some 300 copies of each have been sold. The simplified versions are currently being reviewed and should be published in 2018.

In addition, they expect to publish Volume 5 in both traditional and simplified characters at the same time.

But this does not complete the work. The committee’s ambitious plan includes publishing a total of 15 volumes, which will encompass almost 25 volumes of the American Edition of Luther’s Works. Arranged by subject, Volumes 1–2 cover Luther’s career as a reformer and include texts such as the 95 Theses, the Heidelberg Disputation, the Bondage of the Will and the Leipzig Debates. Volumes 3–5 contain works related to the church and society, while the remaining volumes (6–15) will include commentaries, sermons, worship, liturgy and writings on the Sacraments.

Over the years, this ongoing project has been supported by the LCMS and individual donors, and it also received early funding from the Schwan Foundation.

Yeung said that the texts are being used primarily by church leaders, pastors, seminaries, university teachers and students, and Christian and non-Christian scholars.

However, the Rev. Carl Hanson, LCMS missionary and director of Operations for the Asia region, noted that they even heard that the texts are being used a bit farther afield: “We did hear interestingly that when Vol. III and IV came out, there were Chinese-speaking communities in Malaysia that were using the books as part of their theological studies.”

Hearing the Good News through Luther

Even though the effort and staff required to complete a volume is monumental, the value cannot be counted. Rowold explained that Chinese law restricts access to Bibles to churches. As academic works, however, the works of Martin Luther are widely available in bookstores and libraries.

University students and scholars in China can read and hear Luther’s teaching on the Word of God, the justification of the sinner, the role of the Christian in society, and so much more. Since Luther was a man of the people in many ways, Chinese students desire to learn more about him.

Luther’s adamant insistence on placing Christ at the center of his work ensures that anyone who reads him will undoubtedly encounter the message of God’s work for man through Jesus Christ. The CELW is not only fulfilling Yeung’s hope to “train more [Chinese] Luther scholars,” but it also is providing opportunities for Chinese Christians to hear and receive Luther’s legacy.

Yeung sees this as a central piece of this project. “Luther’s legacy belongs not only to the Western world, to Germans or to Americans, but it also belongs to the Chinese,” he said.